By Rafael Chavez MD

CASE INTRO

It is another busy Saturday night in the trauma bay. You get a call from EMS that they are bringing in a freeway driver in a rollover MVC that required a prolonged extrication.

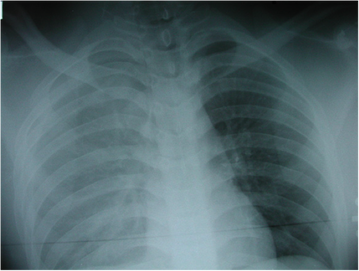

Upon arrival, he is GCS 14, HR 125, BP 109/75, RR 28, SpO2 95%. On primary survey, you note decreased breath sounds on the right side with chest wall crepitus. After completing your primary and secondary surveys, you determine the patient is stable for CT and obtain portable chest and pelvis x-rays before sending him off to the scanner.

Concerned for chest pathology, you look at the CXR below and immediately know you’ll have to put in a right-sided chest tube when the patient comes back from CT.

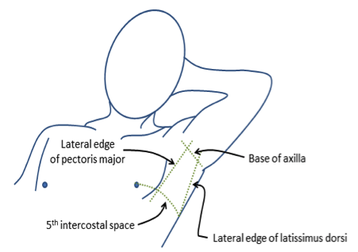

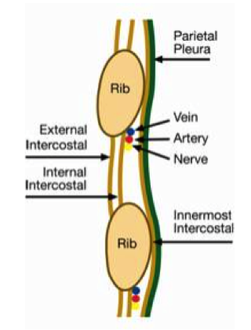

Chest tubes are placed in the ED for variety of traumatic and atraumatic pathology (e.g. pneumothorax, hemothorax, empyema, etc). Recall your rib anatomy and that the neurovascular bundle runs below the rib, so you’ll enter the pleural space over the rib. A chest tube is placed in the lateral chest wall in an area called the “triangle of safety,” which is made of the borders of pectoralis major, the nipple line (5th intercostal space), and latissimus dorsi.

|

|

It was traditionally taught that a traumatic hemothorax required a larger sized chest tube (36-40 Fr), but recent literature has shown smaller chest tubes (28-32 Fr) to be just as effective (1). Recent studies have also shown that spontaneous and traumatic pneumothoraces can be effectively managed with small-bore pigtail catheters (6-12 Fr) and a Heimlich valve, sometimes as outpatient. When compared to large bore chest tubes, pigtail catheters were found to be equally effective, more comfortable, and have fewer complications. (2,3,4,5)

See the “deep dive” PDF reference for step-by-step instructions and more detailed information about the procedure!

CASE CONCLUSION

The patient returns from CT and luckily remains stable. CT is read as multiple right-sided rib fractures, a moderate-sized right hemothorax, and a grade II liver laceration. A right-sided chest tube is placed without difficulty under procedural sedation using ketamine. The chest tube puts out 700 mL of blood initially and only 100 mL over the next two hours. You remember that immediate drainage of ~1500 mL of blood upon tube placement or ~200 mL/hr afterward is an indication for thoracotomy. He is then admitted to the SICU for further care.

References

Inaba K et al. Does size matter? A prospective analysis of 28-32 versus 36-40 French chest tube size in trauma. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2012; 72(2):422-7

Benton IJ, Benfield GF. Comparison of a large and small-calibre tube drain for managing spontaneous pneumothoraces. Respir Med. 2009 Oct;103(10):1436-40.

Dull KE, Fleisher GR. Pigtail catheters versus large-bore chest tubes for pneumothoraces in children treated in the emergency department. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2002 Aug;18(4):265-7.

Gammie JS et al. The pigtail catheters for pleural drainages: a less invasive alternative to tube thoracostomy. JSLS. 1999 Jan-Mar;3(1):57–61.

Hassani B, Foote J, Borgundvaag B. Outpatient management of primary spontaneous pneumothorax in the emergency department of a community hospital using a small-bore catheter and a Heimlich valve. Acad Emerg Med. 2009 Jun;16(6):513-8.

Roberts, James R, Catherine B. Custalow, Todd W. Thomsen, and Jerris R. Hedges. Roberts and Hedges’ Clinical Procedures in Emergency Medicine. , 2014. Print.